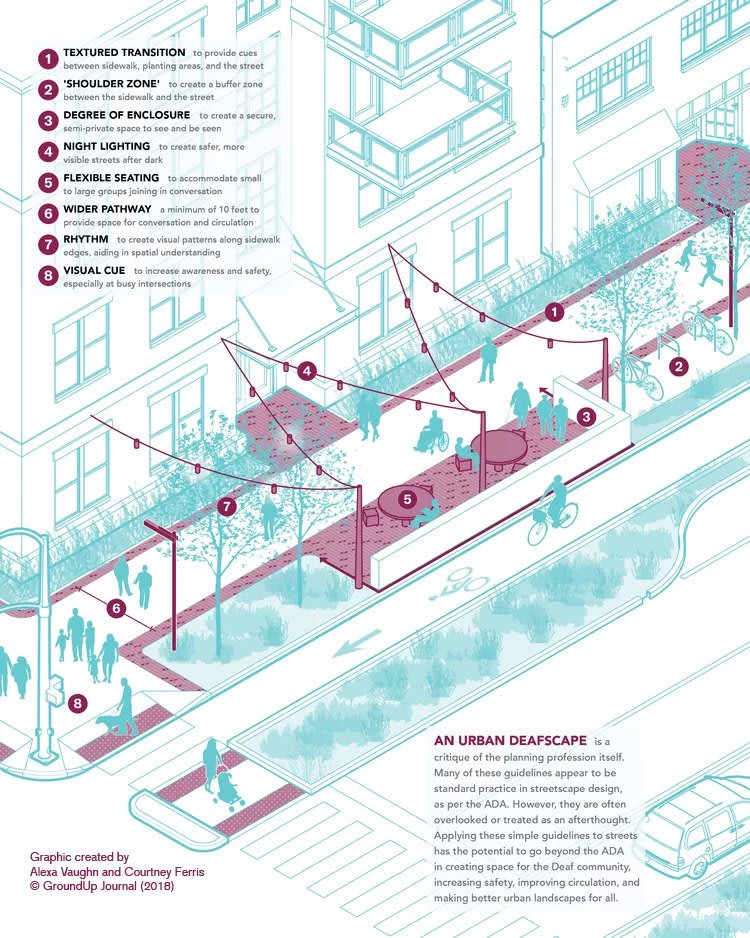

Alexa Vaughn’s DeafScape concept calls for streets with public seating, vegetation, bright lighting at night, tactile cues, and wide sidewalks.

ASLA’s Universal Streets section incorporates Vaughn’s concepts and picks up where the already-robust guidelines for complete streets leave off by centering people with different ability levels.

Universal Streets are multi-modal and include pedestrian islands. ASLA’s guidelines specify wide sidewalks to allow enough room for people in wheelchairs to turn around or rest and for people using sign language to face each other and communicate without impeding foot traffic.

Universal streets also include frequent seating with arms so that people can rest and easily lift themselves; flexible seating so people can choose where they want to sit; good lighting that minimizes shadows, which can be perceived as grade changes by people with low vision, and glare which affects people with sensory sensitivity. Universal streets have visual patterns to them so that people can easily navigate and understand them, as well as tactile cues for people with low vision.

ASLA’s best practices call for areas for socializing, complete with shade and seats, and enclosed areas of refuge for people with sensory processing issues. It suggests trees and plants to help attenuate acoustics. As Alysia Abbot, the parent of an autistic child wrote in a recent Curbed feature about parks and accessibility, green space is vital for people on the autism spectrum or who have sensory disorders.

”We made the case that green infrastructure—the ecological element—should be part of universal design,” says ASLA’s Jaren Green, who co-authored the guidelines. “Nature benefits everyone across abilities. Research shows exposure to nature provides cognitive benefits, improves mood, and creates a sense of greater well-being. If someone is finding accessing or traversing the built environment stressful, to begin with, it makes sense to reduce the stress through adding greenery without adding obstacles.”

Some of these streets already exist, like Bell Street Park, a shared street in Seattle, and Jackson Street, the recently redesigned thoroughfare in St. Paul.

Appropriating assistive design en masse can make the world work better for everyone, a concept designers call the “curb-cut effect.” One of the first-ever curb cuts—those areas where the sidewalk slopes down to meet the street at intersections—was built in Michigan in 1945 to help to return World War II veterans with disabilities. Now they’re common fixtures, which allow people with strollers, suitcases, carts, and more to use sidewalks more easily. Adopting universal streets could lead to a similar effect. Greener streets, more welcoming streets, more places to sit, more places to retreat, and more places to just exist would improve the quality of life for everyone.

“The public realm is the most critical space to design for equity and access simply because it is the largest scale we can work at and it affects the largest amount of people daily,” Vaughn says. “If we focus on how to design for different bodies in the public realm, we can move toward creating holistically accessible cities.”